The Hotel Speicher am Ziegelsee on the "old harbour", today a four-star superior hotel with distinction, was a granary with just such a use until the early nineties.

Built in 1939 by Paul Ohlerich as a Reich-type silo for eternity. During the Third Reich's reign of terror, the Jewish limited partners and company founders, the Löwenthal and Nord families, were expropriated. Paul Ohlerich, who had joined the company a few years earlier, acquired Löwenthal & Nord during the Nazi era.

We would like to give Annie Löwenthal's great-granddaughter, Annette Jonas, a chance to speak and are publishing her speech, which she gave in 2024 at the laying of the Stolpersteine for the Löwenthal family in Schwerin.

We are happy to have contact with the family today.

Speech by Annette Jonas on the Stumbling Stones

Dear Mayor Badenschier, dear Schwerin residents, dear friends and my dear family. My name is Annette Galula, formerly Jonas, and I am originally from Minnesota, but have lived in Israel for 42 years. Thank you all for coming.

We are here to remember Otto and his family, who were systematically terrorised and then brutally murdered by the Nazis simply because they were Jewish. Our grandmother Annie was Otto's sister, so we are the great-nieces and great-nephews of Otto Loewenthal and his wife Elli and the cousins of their children Renate and Eddie-Peter. The Stolpersteine will ensure that they are not forgotten, and my family and I are grateful to all the people who have made this possible.

Otto Carl Joseph Loewenthal was born in Schwerin in 1899 as the middle child of Gustav and Emilie Loewenthal. Unlike his older sister Annie, our grandmother, who wanted to become a teacher, or his younger brother Rudolf, who had completed a doctorate, Otto was not interested in an academic career. He served as a soldier at the front during the First World War and after the war he was in the Home Army.

In 1926, Otto became a partner in the successful company "Loewenthal & Nord Co.", which had been founded by Otto's grandfather in 1855. Otto worked together with the two other Jewish senior partners, his father Gustav and his cousin Max Nord, who together owned 75 % of the company. The remaining 25 % of the company belonged to Paul Ohlerich, who was not Jewish.

In 1930 Otto married the woman he loved, Elli Agnes Aron from Berlin. Otto and Elli had three children; Renate, their eldest, was born in 1931; next came Heinz Günter, who was born in 1933 but died of heart failure in 1936. Their youngest son, Eddie-Peter, was born in 1938.

In the few photos we have of Renate Mary Loewenthal, you can see from the gentle expression on her face that she was a special little girl. When I was a young girl, I found a beautiful profile photo of Renate in an old album that my father was allowed to take with him on the Kindertransport from Germany. I asked my father who she was and he told me that Renate was his pretty younger cousin, who he liked to play with when the family got together. Dad told me that Renate had a little brother who he loved to hold in his arms. This baby was Eddie-Peter, born in the spring of 1938. Unfortunately, no photos of Eddie-Peter have survived, so we have no picture of the once beloved boy.

Before 1933, Otto, Elli and Renate led a quiet and peaceful life in their flat right here on Demmlerplatz, just an eight-minute walk from Loewenthal & Nord Co, which meant that Otto could spend more time with his beloved wife and daughter. But that all changed when Hitler came to power and the three Jewish partners - Otto, his father Gustav and Max Nord's widow - were forced out of the company. Paul Ohlerich became the sole owner and brought his son Joachim Ohlerich into the company, which he renamed "Ohlerich & Sohn". The Ohlerichs, who were once business partners, neighbours and friends of the Loewenthals and Nords, were to betray this relationship for decades.

As they were no longer welcome in Schwerin, Otto, Elli and Renate sought refuge in Berlin. Otto's parents, Gustav and Emilie Loewenthal, who lived in their beautiful villa in Alexandrinenstraße, just a 15-minute walk away, were not welcome either. This became clear when Schwerin residents wrote slogans on the walls of their villa, such as "Jew out" or "Throw this Loewenthal into the lake!". Gustav and Emilie sought refuge in Hamburg, where Emilie was from. Gustav died in 1935, and in 1938 Emilie committed suicide by hanging herself in her rented room. Our Loewenthal family had lived in Mecklenburg for around 300 years, but the inhabitants of Schwerin turned their backs on the Jewish family who had come here in 1860 and had contributed to the prosperity of the region, among other things by supplying the people of Schwerin with much-needed food during the First World War.

Over time, the conditions for Jews in Germany became unbearable. Otto's bank accounts were confiscated and switched to blocked accounts. Renate could no longer go to school, Otto and Elli were not allowed to buy everyday necessities, they had to wear a yellow star, were not allowed to enter certain parts of Berlin and a curfew was imposed; the list of over 2,000 anti-Jewish laws is too long to list them all. Otto realised that he had to leave Germany with his family, but the emigration process was incredibly lengthy and full of hurdles. To make matters worse, Otto had been conscripted into forced labour from May 1940 to September 1941. Otto turned to the American embassy in vain and was only granted a tourist visa for Cuba in October 1941, but it was too late. From August 1941, the Nazis banned Jews between the ages of 18 and 45 from leaving Germany. Renate and Eddie-Peter did not belong to this age group, but Otto and Elli did, and they could not bear to send their children away alone.

In the end, Otto and his family received their deportation notices for "resettlement" to the East. The Jews believed they were being resettled and had never imagined the Nazis' plan to systematically murder them and rob them of everything they owned. The "resettlement" was a Nazi deception on the grandest scale to prevent any Jewish resistance that could have slowed down the Nazi killing machine.

Otto and Elli packed the few belongings they were allowed to take with them and, together with Renate and Eddie-Peter, they had to gather with other Jews in the former Jewish old people's home in Große Hamburger Straße, which had become a prison for Jews before the deportation. All the furniture had been removed, the toilet doors had been removed and the windows had been fitted with iron bars, and the building was fenced in with barbed wire and floodlit at night. Policemen were posted in the building with orders to shoot anyone who attempted to escape. The Jews imprisoned there had to fill in a declaration of assets, which the Nazi Reich used to confiscate all their remaining property and assets.

The destruction of Otto and his family also involved the theft of all their possessions, possessions that pass on personal history from one generation to the next. Apart from a few photographs, we have no valuable items that Otto and his family once held in their hands. We discovered that there are six silver forks with the letter "L" engraved in the handles that belonged to our great-grandmother Emilie Loewenthal in the Folklore Museum here in Schwerin. While these six forks are of little value to the museum and the people of Schwerin, they have great emotional value to us as tangible evidence of the family's existence.

After being locked up for days in the Große Hamburger Straße collection camp, Otto, Elli, Renate and Eddie-Peter were driven to Putlitzstraße station in the Berlin district of Moabit, where they were crammed into closed cattle wagons on 12 January 1943. It was a terrible journey in cattle wagons, in which hundreds of people were crammed together without food, water or toilets.

There are documents according to which Otto and Elli were murdered in mid-February. So we can only conclude that Renate and little Eddie-Peter were somehow separated from their mother during the chaos when Jews were brutally driven out of the cattle wagons after their arrival in Auschwitz. Renate and Eddie-Peter were then pushed from the platform at Auschwitz into the waiting lorries that took them, along with the elderly, sick and mothers with small children, straight to the gas chambers and crematoria, where they were all gassed within a few hours. Of the 1,196 people who were deported on the 26th transport on 12 January, only two survived.

One can only imagine the indescribable agony of Otto and Elli's last month of life, knowing that they could not save their beloved children from such a cruel death. Renate and Eddie-Peter fought for their last breath without their mum by their side; this image will haunt me for the rest of my life. Renate was just 11 years old; it is not inconceivable that she could still be alive today at the age of 92. Eddie-Peter was only 4 ½ years old, the same age as my grandson. So I can imagine that Eddie-Peter, like my grandson, still had baby-soft skin, but was at an age where he was fully aware of his surroundings and could hold conversations with loved ones and strangers. It is very likely that Eddie-Peter could still be alive today at the age of 86. Renate and Eddie-Peter were robbed of their right to grow up, to experience the love of a spouse and children, and to fulfil their own special potential as human beings.

The murder of Otto and his family left a huge gap in our family. Otto's older sister Annie, our grandmother, fled to China and had to live in the Shanghai ghetto for six long years before moving to the USA. Otto's younger brother Rudolf also survived the war in China, but never had any children. Elli's only sibling, who fled to New York before the war, also never had children. Elli's mother managed to flee Germany at the last minute and eventually made it to New York, where she died of a broken heart. Our grandmother Annie was the only one in our Loewenthal family who survived the Holocaust with children. Her two sons, Gershon and Peter, survived the war far from the loving care of their mother and lived on two different continents; my father Peter in England and Ronit's father Gershon in pre-state Israel.

Finally, by a crazy twist of fate, we learnt about the laying of the Stolpersteine for Otto and his family from the grandchildren and great-grandchildren of the Ohlerichs, who are here today. They were the initiators of the laying of the Stolpersteine and informed us, the surviving members of the Loewenthal family, about this ceremony.

We are grateful to everyone who has come here today to honour the memory of Otto, Elli, Renate and Eddie-Peter. We hope that their memory will never be forgotten by the people of Schwerin and by others; they will certainly never be forgotten by us.

The years were characterised by the urban planning orientation of the harbour area. The first investors showed interest in the area. In these early years, exposed building plots around the hotel appeared as partially blossoming meadows.

The original harbour/warehouse development plan from the city of Schwerin was deemed outdated. The initial plans and approvals granted in the neighbourhood unfortunately led to a very long, tough struggle with the investor and the City of Schwerin. A solution was finally agreed upon. As a result, between 2010 and 2014, mainly terraced houses were built in the immediate neighbourhood instead of multi-storey residential buildings.

A lot has happened in the old harbour area in these years. Numerous freehold flats have been built almost as quickly as the new SWS public school, which was built in just a few months.

Just a few years later, another school "Nordlichter" was completed opposite the hotel.

In 2014, after more than 18 years, the reallocation committee of the city of Schwerin was actually able to finalise the last reallocation.

In 2013, the city finally began to renovate the lakeside promenade along the Ziegelsee, which had been planned years ago and was eagerly desired by all residents, in order to reconnect the "old harbour" more closely to the heart of the city.

This successful refurbishment project was completed in May 2014. At the same time, the hotel's own jetty was completely renovated. Weisse Flotte and the hotel agreed on a regular timetable between the hotel and the castle. The jetty is also available to hotel guests as a bathing jetty. The new footpath along the edge of the former brewery site has also been completed. Now our guests can easily reach the old town centre on foot along the banks of the Ziegelsee in about 10-15 minutes!

Despite the coronavirus pandemic, densification in the harbour continued diligently until 2024. Almost everything has now been built on, except for the neighbouring plot next to us. This project coincided with the construction crisis and was stopped.

Many would like to see more green spaces and a playground instead of further development. We remain curious.

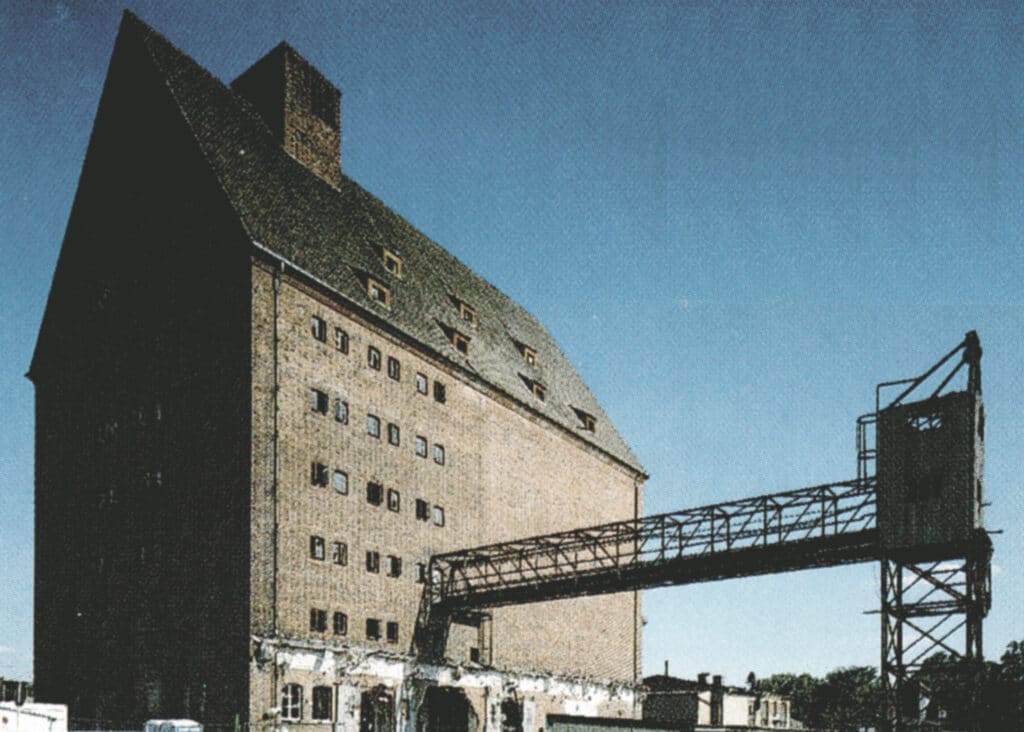

The existing 6000 tonne grain store building was constructed as a solid reinforced concrete structure surrounded by a brick outer shell. From the initial planning phase, great importance was attached to preserving the original character of the listed granary.

Two thirds of the storage facility consisted of reinforced concrete silo cells, which extended from the basement to the 7th floor. The honeycomb-shaped reinforced concrete silos posed a major challenge for the planners and contractors.

The demolition of the silo cells, which took up the entire southern part of the building, was literally a tough job in view of the concrete walls, some of which were over 1 metre thick. The construction style of the Third Reich and the associated concrete quality and the amount of steel used had been underestimated.

The parallel installation of steel scaffolding inside the building was also important to prevent the building envelope from collapsing. The steel constructor and demolition contractor had to work simultaneously and independently of each other.

The steel construction created a "house within a house" principle in the southern part of the building, which was honoured with the Steel Innovation Award in 1996.

The warehouse is a listed industrial building. This fact influenced the construction process with regard to the choice of materials and colours for the outer building shell. If you consider the height of the water level of the Ziegelsee lake, it quickly becomes clear that the warehouse with its 1.50 metre thick concrete floor is "in the water". A casemate encloses the basement like a watertight tank

After completion of the demolition work and finalisation of the load-bearing steel skeleton structure, the building was completed in 12 months. The aim of the conceptual considerations for the extension of the building was to reflect the individuality and uniqueness of the building in the hotel rooms and public areas. For example, the old reinforced concrete mushroom head supports are visible as a supporting architectural detail in the rooms in the northern section. The strict window layout and the load-bearing pillars determined the internal layout of the guest rooms. This resulted in the different room layouts, in which a wall sometimes had to "jump out" for a window opening. For the entire interior fit-out, emphasis was also placed on using predominantly natural materials.

95 % of the room furnishings, such as lamps, tables and beds, were specially manufactured with a view to a simple style appropriate to the house. The old wooden windows were lovingly restored and the demolished hand-moulded bricks were reused for the lintels and the bar area. The use of burnished iron in many details is intended to visualise the history of the industrial building today.

When the hotel opened in August 1998, Speicherstrasse was still a "sandy track" and the hotel was directly surrounded by old factory buildings. In October 1999, the demolition of the former window factory in Speicherstrasse opposite the hotel began, but the owners of the hotel were allowed to wait until 2004 for the final extension of Speicherstrasse with the connection to Güstrowerstrasse. Until then, the entire supply and disposal of the hotel had to be ensured by the owners' own initiative. Regular guests who have been coming to us since the hotel opened can still tell us about the industrial wasteland that surrounded the hotel.